Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Impact of Forensic Accounting on Fraud Detection in Zimbabwes Public Sector Expenditure Cycle

Authors: Gibson Tangai Murinda, Ronald Chiwariro

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2023.57067

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

The objective of this study was to evaluate the influence of forensic accounting on the discovery of fraudulent activities within the public sector of Zimbabwe, specifically examining the expenditure cycles of government departments. The investigation was sparked by the Auditor General\'s disclosure of governance problems and the rise in qualified audit opinions observed from 2018 to 2022. During that time period, the government imposed additional restrictions, such as a directive to freeze payments for all contracts that had been submitted for payment, a requirement to conduct due diligence checks on all contracts with the assistance of internal audit staff, and the blacklisting of 19 companies in an effort to get value for money, as well as a reduction in the huge appetite for business travel by government officials (Treasury Circular number 5 of 2023) served as another impetus for the research. The study\'s objective was to evaluate how forensic accounting affects fraud detection and make recommendations on the most effective practices that Forensic Accountants can use. The study employed a descriptive design, grounded in a positivist philosophical framework. The study suggested that the government should integrate forensic accounting services within its organizational structures. This allows distinct departments to work independently without interfering with one another. There is also a need to develop clear policies to govern forensic accounting practice in the public sector. Consequently, it is imperative for the government to contemplate the establishment of Forensic Accounting Departments inside each of its ministries and state-owned enterprises, with the aim of identifying instances of fraudulent activities within the government\'s expenditure process.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

Governments employ the procurement process to buy goods and services required for the effective operation of their entities. This renders public spending vulnerable to fraud and corruption. Globally, the incidences of fraud are rising rapidly in both the private corporate and governmental sectors. According to the ACFE Occupational 2022 report, there were 2110 incidences of fraud that were discovered in 113 countries around the world, resulting in losses of more than $3.6 billion. Many frauds continue to go undetected for extended periods of time, despite improved fraud prevention and detection techniques. According to Albrecht et al. (2015), fraud comprises any dishonest methods employed by one individual to gain an advantage over another through fabrication. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) predicts that, on average, businesses will lose 5% of their annual revenue to fraud in 2016.

This illustrates how widespread fraud is on a worldwide scale. Any employee, regardless of their level, has the capacity to commit internal fraud. They can range from little thefts of travel funds to large-scale scams involving extremely lucrative contracts and control violations that could have major and noticeable effects. (World Bank Centre for Financial Reporting)

In an effort to prevent financial crimes within the public entities in Zimbabwe, the government mandated that the Auditor General disclose to the legislature on the results of the review of all public entities' accounts. This obligation is enhanced by the Constitution of Zimbabwe and the Audit Office Act [Chapter 22:18]. The opinion expressed in the auditors' report is intended to provide a reasonable level of certainty regarding the absence of major misstatements in the financial statements taken as a whole, whether as a result of fraud or error.

The AG reports, which cover financial statements that comprised appropriation accounts, finance and revenue statements, and fund accounts, for the fiscal years 2018 through 2022 emphasize the key audit findings and recommendations. Table 1.1 below provides a summary of the governance issues raised and the qualified audit opinion reported by the AG between the financial years 2018 and 2022 Appropriation accounts:

Table 1: Summary of Governance Issues Raised and Qualified Opinions Issued

|

FINANCIAL YEAR |

GOVERNANCE ISSUES RAISED |

QUALIFIED OPINIONS ISSUED |

|

2018 |

13 |

15 |

|

2019 |

8 |

17 |

|

2020 |

105 |

19 |

|

2021 |

97 |

17 |

|

2022 |

168 |

38 |

|

TOTALS |

391 |

106 |

A total of 391 governance issues were raised whilst 106 qualified opinions were issued. The total number of governance flaws and qualified audit opinions raises recognizable red flags for financial crimes The AG offered recommendations on how to address the problems raised in order to improve service delivery, transparency, and accountability in the government sector. The audit looked at aspects of governance, revenue collection and debt management, employee compensation, the purchase of goods and services, asset management, gender policy, and supporting structures. This is in light of the Government of Zimbabwe's emphasis on service delivery as stated in the National Development Strategy (NDS 1), the AG urged those in charge of governance in the various institutions to pay attention to the issues raised in order to improve public sector transparency, accountability, and service delivery. This demonstrates that, despite attempts by governments and other regulatory bodies to prevent fraud and corruption, it is pervasive and calls for additional investigation. According to Madziva, Msipah and Tukuta (2022), the government of Zimbabwe gazetted about ten Statutory instruments between 2018 and 2021 to try and stabilize the market environment. Despite the existence of some restrictions, public officials influence tender processes for their own benefit (Chigudu 2014).

Worldwide, organisations of all types and sizes face a common problem due to fraud (ACFE, 2018). Worldwide, organisations of all types and sizes face a common problem due to fraud (ACFE, 2018). The implementation of solid internal controls is often regarded as the most effective approach within government entities to mitigate instances of fraud. Notably, the government of Zimbabwe is successfully employing such measures every year. In August 2022, the Ministry of Finance issued two directives. The first directive, labelled MoFED/C/99/1, pertains to the freezing of payments for all submitted contracts. The second directive, labelled MoFED/C/99/2, outlines instructions for conducting due diligence exercises on contracts, specifically through the utilisation of internal audit staff. In November 2022, a governmental action was taken to blacklist a total of 19 enterprises with the aim of optimising cost-effectiveness in the realm of public procurement. Treasury Circular No. 5 of 2023, which came into effect in February 2023, aimed at mitigating the substantial inclination towards international business travel among government personnel. An additional circular (Treasury Circular No. 6 of 2023) was released by the government to give guidelines on the prices of goods and services acquired by the government.

This emphasises the significance of forensic accounting in the identification of fraud because a strong internal control system cannot ensure that fraud won't occur within organisations. According to the ACFE (2022), fraud costs businesses throughout the world trillions of dollars annually. As a result, the complexity of fraud in today's world is increasing, necessitating a close examination and the use of more advanced detection methods. As a result, forensic accounting techniques are now important in the fight against financial crimes like fraud (ACFE Report to the Nation, 2014). The goal of forensic accounting is to ascertain whether a person or an organization has been involved in any financial crime activity, such as corruption, bribery, fraud, and money laundering.

The Zimbabwe government maintains strong internal controls by ensuring that each and every ministry have internal auditors and ensuring that tasks performed by auditors within is further reviewed by the Auditor General yearly with a view of reducing fraud. The Auditors conducts their evaluations in compliance with the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAIs) and the International Standards on Auditing (ISAs). Audits must therefore be planned and executed in accordance with these Standards in order for auditors to have a reasonable certainty that there were no material misrepresentations in the financial statements. The audit approach is developed to enable the expression of an opinion about the financial statements of government departments. It is believed that management should be in charge of maintaining effective internal controls, thus it's possible that not all of the entities' actions and processes will be reviewed. It is clear that that the auditors’ work will not identify all weaknesses in the procedures and systems. Since audit plans are created with the possibility of fraud in mind, the auditors need to anticipate that they will have a realistic expectation of fraud in their disclosure if the probable impacts of the fraud will materially affect the financial statements (AG 2021 Report).

Between September 2022 and April 2023, the government via the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development as the custodian of resources procurement, issued a variety of measures in an effort to achieve value for money in public. These included negotiation for price downward on all contracts, a requirement for due diligence before payments were effected and blacklisting of suppliers. This reflects lack of faith in the traditional auditors and that an audit opinion is not an affirmation that the financial statements are accurate, rather it is based on the idea of reasonable assurance.

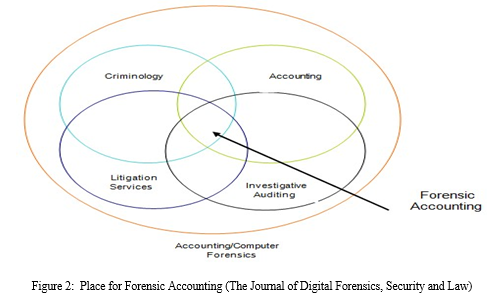

It would be impossible to expect the typical audit to find all forms of fraud, especially those involving defalcation, forgeries, cooperation, and managerial override of controls. The principal objective of audit procedures is to enable the expression of an opinion on the truth and fairness of the financial statements as a whole. As such the government should consider a shift from the traditional statutory auditing perspective to forensic auditing so as to lessen the fiscal and monetary losses sustained by the economy as a result of financial crimes such as frauds. Figure 2 illustrates the status of investigative accounting as well as auditing in respect to the fields of accounting, auditing, criminology, and litigation services.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

A. Definition of Forensic Accounting

According to Crumbley, Heitger, and Smith (2005), the definition of "forensic" is "suitable for use in a court of law," so accountants typically have to adhere to this criterion and its potential results. Maurice E. Peloubet first used the term "forensic accounting" in his 1946 essay, "Forensic Accounting: Its Place in Today's Economy." Forensic accounting deals with engagements resulting from ongoing or potential legal disputes or litigation.

According to Arokiasamy and Cristal (2009) and Dhar and Sarkar (2010), forensic accounting is the field that uses accounting facts and ideas learned through auditing methods, strategies, and procedures to solve legal problems. Stanbury and Paley-Menzies (2010) say that forensic accounting is the field that gathers information and presents it in a way that a court of law will accept in order to prosecute people who commit economic crimes.

The term "forensic accounting" refers to services that make use of the specific expertise and investigation skills that CPAs have, according to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). Forensic accounting services make use of the practitioner's specialist accounting, auditing, economic, tax, and other expertise (AICPA, 2010). Singleton and Singleton (2010) propose a holistic approach to fraud detection that encompasses non-financial data acquisition, antifraud control analysis, and fraud prevention.

B. Forensic Accounting Perspectives

The definitions in 2.1 state that the objective of forensic accounting is to locate and look into any suspicious activity in order to ascertain the real motive of the offender. It is feasible to conduct interviews, review documents, go at electronic files, and conduct other kinds of reviews. Forensic accounting, from the standpoint of an auditor, is the use of auditing methodologies, techniques, or procedures to resolve legal issues that necessitate the merger of investigative, accounting, and auditing expertise (Arokiasamy and Cristal-Lee, 2009; Dhar and Sarkar, 2010). From the perspective of a legal expert, forensic accounting includes gathering, deciphering, summarising, and presenting complicated financial concerns in a clear, succinct, and factual manner, usually in a court of law as an expert. (Howard and Sheetz, 2006; Stanbury and Paley Menzies, 2010). A court of law will accept such forensic evidence only if it complies with the rules set forth by legal authorities. According to a fraud examiner, forensic accounting is the use of analytical and investigative skills to settle financial disputes in a way that complies with legal requirements (Hopwood et al., 2008). Finally, a forensic accounting inquiry will require the services of an experienced auditor, attorney, and fraud examiner.

C. Fraud Defined

Fraud is a worldwide problem that influences businesses everywhere. (ACFE, 2020). Studies have used a variety of definitions of fraud due to the fact that different individuals and organisations have varying perspectives on what constitutes fraud (Baldock, 2016). Similar to this, Lokanan (2015) defines fraud as a complex situation with supporting background that is not restricted by any particular theoretical framework. Kurpierz and Smith (2020) contrasted this by stating that "fraud is a colloquial and technical term that is used as an umbrella system to describe a large number of dishonest and harmful behaviors." The cost of fraud therefore goes beyond merely monetary loss to include collateral damage such as harm to customer relations, staff morale, corporate integrity, and branding (Bierstaker et al., 2006). Therefore, the term "fraud" is used to refer to all unethical actions taken to gain an unfair advantage over another person. Additional components of fraud, according to Kranacher and Riley (2019), include enormous deception, information that the assertion was false at the time it was made, victim reliance on the misleading claim, and damages as a result of the victim reliance on the false statement.

Both defining and identifying fraud are challenging tasks. It is impossible to establish a clear-cut, constant norm that defines fraud because it includes all sly, dishonest, and unjust methods of defrauding someone. Fraud is the term used in law to identify intentional falsification of the truth in an effort to persuade or mislead an entity or individual. It happens when someone signs a contract while still under the influence of a misleading perception or after receiving inaccurate information. David (2005) asserts that fraud is more likely than it is possible. He also demonstrates how group decision-making may be more effective at preventing fraud than individual judgment.

If everyone in the group is thinking about the same thing, though, this is not the case. As a result, fraud might not be stopped. On the other side, the dominant decision-maker, who ultimately controls all decisions, has an impact on the group. According to Russell (1978, cited in Bello, 2001), the term "fraud" is broad and applied in a number of contexts. Because fraud can take on so many different degrees and forms, courts are forced to confine themselves to a small number of general guidelines for identifying and thwarting it.

D. Famous Frauds

- Enron Fraud

The Enron scandal was brought on by false financial reporting by Enron's executives and auditors. At the time of the scam, Arthur Andersen was one of the "big five" accounting companies. Enron hid this deception by delaying the release of necessary financial documents for over six years, including a balance sheet and an income statement. This created scepticism and hastened Enron's demise. By eliminating particular transactions and failing to declare contingent liabilities, Enron was able to transform a 2001 net loss into a net income of $393 million. Lack of independence between Enron and Arthur Andersen, who were performing non-audit work for Enron, was the root of this deception. This fraud was caused by a lack of independence between Enron and Arthur Andersen, who were doing non-audit work for Enron. This led to changes in auditing standards and the way auditors are monitored, making it illegal for CPA firms to perform non-audit services for their audit clients.

2. WorldCom Fraud

The second-largest long-distance telephone provider in the US, WorldCom, filed for bankruptcy in 2002 as a result of false financial reporting. For their roles in the scam, Bernard Ebbers and Scott Sullivan received prison sentences, while 17,000 employees lost their jobs. By wrongly capitalising $3.8 billion in operating expenses and performing transfers between internal accounts that did not follow GAAP, WorldCom was able to change their financial statements.

3. Hulett, Tongaat Scandal

Both the London Stock Exchange and the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) suspended Tongaat Hulett, the oldest and largest sugar producer in South Africa, for inflating the company's valuation by R3.5 billion to R4.5 billion in its 2018 financial reports.

4. Bosasa

Between 2003 and 2018, Bosasa got R12 billion in government contracts. According to the Mail and Guardian, the firm overcharged more than 40 provincial and federal government departments, and the state was obliged to pay R161 for security gate remote controls. It was able to acquire contracts worth millions of dollars by using its contacts with state workers. Angelo Agrizzi, the former COO of Bosasa, detailed in February 2019 how they had influenced state procurement by bribing Zondo commission officials.

5. ZESA Frauds

In October 2018, three Zesa executives were charged on two counts of defrauding the parastatal of more than $111.8 million through a procurement scam and appeared in court at the Harare Magistrates' Courts. According to the Herald newspaper, the Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority (Zesa) discovered a scandal in February 2021 over the manipulation of its subsidiary, Zimbabwe Electricity Transmission and Company (ZETDC), by its employees who were fraudulently generating electricity tokens. It was reported that the corrupt activities have been going on for years and that a number of people have been fired for defrauding the company of revenue through the billing system. The Chronicle newspaper further stated that some ZESA employees were also arrested in February 2022. The four ZETDC employees based in Plumtree were arrested for allegedly defrauding the company of fuel worth USD 5000.00.

6. NSSA Frauds

In its audit of NSSA's financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2018, the Auditor-General (AG) expressed a negative audit opinion, indicating that the company's financial statements are inaccurately stated and misrepresented and do not accurately reflect its true financial performance. According to the Herald, the National Social Security Authority (NSSA) director of corporate affairs appeared in court in August 2022 to answer charges of allegedly duping the entity of over US$180,000. In February 2023, the director of investments was suspended for a suspected scandalous acquisition of properties. This shows that NSSA personnel at the highest levels have been accused in corruption cases involving millions of dollars, eroding the value of citizens' deposits and calling for the services of forensic accounting to establish the truth.

7. ZIMRA Frauds

A Zimbabwe Revenue Authority staffer and a director of a private company were arrested by the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission in September 2021 for fraud involving $84,000 and $26 million. A Plumtree-based ZIMRA official was sentenced to 14 years in prison for fraud involving 389 cars (The Herald).

8. Netone Frauds

According to the Herald newspaper, Three NetOne employees, a bulk airtime dealer and his employee, were arrested and taken to court in January 2023 after duping the state-owned company of US$565 999 964 through the use of a pin-less credit airtime transfer facility.

E. Fraud Detection

When fraud cannot be prevented, fraud detection steps in to identify it as soon as possible after it has been committed (Othan et al., 2015). Due to the increased perception of the risk of getting caught, fraud detection discourages people from engaging in fraudulent activity (Jeppesen, 2019). Fraud detection is crucial in fraud investigation and prevention because the techniques and techniques used for fraud detection may significantly affect the magnitude of the fraud, which may help reduce future fraud occurrences (ACFE, 2020). According to Riney (2018), enhancing and boosting the fraud resistance of vulnerable organisations can be accomplished by combining prevention and detection. Sow et al. (2018) added that prevention is the most affordable method to handle financial loss as a result of deception. Therefore, prevention of fraud refers to actual actions implemented by an organisation to avoid or halt the incidence of fraud (ACFE, 2020). Furthermore, avoiding fraud calls for a set of guidelines that, when combined, reduce the likelihood of fraud while increasing the chance of detecting suspected fraudulent behaviour (Biegelman & Bartow, 2006).

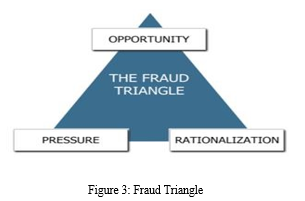

A critical first step in the detection and eventual prevention of fraud is the identification of its causes (Ghazili et al., 2014; ACFE, 2018). Therefore, the following justifications for Cressey's fraud triangle, Wolfe and Herman's fraud diamond, the fraud pentagon, and the fraud hexagon explain why people commit fraud:

- Fraud Triangle

The hypothesis of the fraud triangle, which Donald Cressey devised in 1953, is the most popular fraud theory, claim Lokana and Sharma (2018). This idea was developed as a tool for the identification and avoidance of fraud (Riney, 2018). According to Cressey, each of the three components needs to be present for fraud to take place. The fraud triangle (Lokana & Sharma, 2018) also contains perceived pressure (non-shareable financial pressure), perceived opportunity, and perceived justification (the ability to change one's self-perception). These components together make up the fraud triangle. Figure 3 below demonstrates their simultaneous relationship. However, fraud can still be avoided even if one of the components is missing.

According to Ghazali et al. (2014), perceived pressure is the first part of the fraud triangle. People who felt pressure from the non-shareable financial problem may be motivated to commit fraud by shame or a sense of pride. Only if the person is unwilling to talk about their financial issues is this conceivable (Le et al., 2020). As a result, despite having a lower salary, a person could feel under pressure to maintain their existing standard of living (Zakaria et al., 2016). Additional forms of fraud pressure include greed, massive debt burdens, poor credit, financial losses, and family pressure (Kranacher & Riley, 2019). This manifested itself in the form of manipulatively concealing interests while charging clients exorbitant interest rates. The pressure to commit fraud, however, can come from both financial and non-financial sources, such as a staff member's discontent with their employment (Lokanan, 2018).

The anticipated opportunity is the second element of the fraud triangle. The opportunity is distinguished by the straightforwardness with which fraud is done, as claimed by Biegelman and Bartow (2012). Due to this, perceived opportunity arises in environments with poor internal control systems (Peltier-Rivest & Nicole, 2015; Lokana, 2018; Riney, 2018; ACFE, 2020). Therefore, Biegel and Batow (2012) explain that an institution can minimise fraud opportunities via internal control, thereby eliminating fraud.

The third component of the fraud triangle is the ability of the fraudster to justify their actions as suitable. Rationalisation, according to Chiezey and Onu (2013), is a person's perspective on their work performance, contributions, and anticipated incentives from the company for adding value. Ghazali et al. (2014) claim that rationalisation is the process by which an individual justifies his dishonest behaviour by considering his predicament as a unique circumstance rather than a violation of trust. In addition, Biegelman and Bartow (2012) claim fraudsters always find excuses regularly and portray themselves as victims, saying "they owe me" or "everyone is doing it" to support their behavior. Controlling rationalisation will therefore aid in reducing fraud.

The fraud triangle has been a vital tool for early fraud prevention and detection; however, the fraud theory has come under fire for its failure to address issues connected to fraud. Kassem (2020) asserts that the fraud triangle is useless for assessing financial fraud reports. Kassem (2020) asserts that failure to understand managers' objectives, levels of integrity, and capabilities may result in the failure to detect financial statement fraud. On the other side, according to Lokanan (2015), the fraud triangle is a poor fraud discovery tool. By emphasising this, Lokanan (2015) demonstrates how the fraud triangle fosters a body of knowledge that lacks the objective standards necessary to properly address all fraud-related circumstances. In addition, despite opportunity, pressure, and desire, Biegelman and Bartow (2012) note that some people might not commit fraud. Albrecht et al. developed the theory of fraud scale in 1984 (Dorminey et al., 2012), which replaces personal integrity with logic since they thought it was challenging to characterise fraud. This will therefore be especially true for financial reporting fraud, where there is greater pressure to meet deadlines, earn bonuses, and satisfy analyst expectations (Kranacher & Riley, 2019).

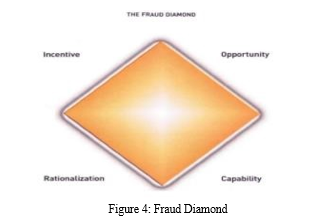

2. Fraud Diamond Theory

In 2004 (Wolfe and Herman, 2004), the fraudulent triangle grew to become the fraudulent diamond. The fraud diamond theory, which makes up the fourth component of competence, is required for the fraud triangle to be complete, claim Wolfe and Hermanson (2004). This is because it may not be possible to perpetrate fraud or cover it up if the weaknesses in control cannot be exploited (Dorminey et al., 2012). The fraud diamond thus enhances the fraud triangle by integrating the fourth factor of competence (Wolfe and Herman, 2004). Additionally, in the framework of the Fraud Triangle, opportunity is modified by the capability construct by restricting the chance to those who have the necessary capability (Dorminey et al., 2012). As a result, Wolfe and Herman (2004) explain that four components incentive, opportunity, rationalisation, and individual capability must all be present for fraud to occur. The following graphic illustrates this.

Wolfe and Herman (2004) highlight the possibility of fraud in a company as a result of lax internal controls or monitoring. However, assuming there was no fraud, the right person lacks the skills to spot an opportunity, be able to take advantage of it, and have the right justification. A person may be able to generate or take advantage of a fraud opportunity depending on their position within the organization. According to Wolfe and Herman (2004), the following characteristics are indicative of fraud:

a. Based on their position within the organization, a person may be able to create or exploit a fraud opportunity

b. Be considered intelligent enough to identify and exploit internal control weaknesses;

c. Possess a strong ego and great confidence;

d. Coerce others to commit or hide the fraud;

e. Be able to tell lies.

3. Fraud Pentagon

The concept of the fraud pentagon was first proposed by Crowe Howarth in 2011, as an extension of the preexisting models of the fraud triangle and fraud diamond. This novel framework incorporates an extra facet pertaining to arrogance. Hence, the elements that motivate individuals to partake in deceitful behaviours, as outlined by the fraud pentagon, consist of pressure, opportunity, rationalisation, capability, and arrogance, as depicted in Figure 5. Arrogant people could think they are exempt from the company's rules.

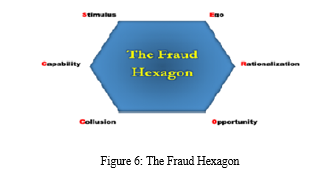

4. Fraud Hexagon

Vousinas (2019) of the National Technical University of Athens proposed the Fraud Hexagon Theory, which evolved from the Pentecostal Theory (SCORE). The fraud hexagon theory identifies six elements—that is, stimulation (pressure), capability (capability), opportunity, justification, arrogance, and collusion—as potential fraud risk factors. According to Achmad, Ghozali, and Pamungkas (2022), there are numerous aspects of theoretical fraud that can be detected. The first is stimulation, also known as pressure, which is the existence of pressure elements both inside and outside of the firm. Financial stability, which has an impact on financial reporting, is how Fathmaningrum and Anggarani (2021) et al. proximate the stimulus. The second factor is capability, which relates to a certain party's capacity to commit fraud, such as the board of directors and corporate executives. A leader's decision-making behaviour is influenced by experience, preferences, and personality. Capacity can be measured by the director's experience. Thirdly, the term "opportunity" refers to someone's potential to conduct fraud, such as when there is insufficient internal control within the organization. The knowledge of external auditors acts as a proxy for opportunity, according to a study by Apriliana and Agustina (2017). The likelihood of financial statement fraud is positively impacted by the knowledge of external auditors. Fourthly, rationalisation can be used to detect fraud by justifying someone's conduct, such as accrual recognition in accounting records. In the fifth instance, arrogance is a symptom of egoism in a person or group in an organisation who typically holds a position. Moving to the sixth point, collusion occurs when two groups come to an agreement with the intention of gaining a profit, while the other group may suffer damages as a result of the arrangement. Aviantara (2021) posits that audit fees exert a collusive influence on financial reporting.

F. Fraud Risk Assessment

Internal fraud risks refer to fraudulent activities perpetrated by individuals or collectives within an organisation, as stated by COSO (2023). External fraud risks refer to instances of fraudulent activities perpetrated against an organisation by individuals or entities outside of the organisation. Organisations that are committed to the prevention, detection, and deterrence of fraud will effectively manage both internal and external fraud risks. Management employs a dynamic process called risk assessment to evaluate the potential hazards involved with achieving its predetermined objectives (COSO, 2013). Risk assessment, as outlined by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB, 2018a), serves as the basis for management's ability to identify company risks through the utilisation of financial reporting. The disclosure of risk assessment roles enables investors to make more informed decisions regarding their investment in the institution (Ashfaq and Rui, 2019).

It is imperative to ascertain the key risks faced by the organisation prior to the implementation of risk management strategies. According to COSO (2013), firms must establish precise objectives that enable the identification and evaluation of risks that are pertinent to the goals. In order to accurately evaluate the risk and address fraudulent activities, it is important to conduct an inquiry into the origin of the danger. Identifying fraudulent activities, such as the creation of fabricated financial statements, can pose significant difficulties. As per the findings of Reding et al. (2012), individuals engaged in criminal activities exhibit a propensity to employ very unconventional methods in order to conceal their illicit actions. However, by detecting fraud red flags and keeping a lookout for warning signals, such as the combination of a weak internal control environment and an inefficient audit committee, fraudulent behaviour may be exposed. Hence, it is necessary to conduct an investigation into fraud risks in order to fully grasp their significance and evaluate their effectiveness.

The information required to carry out the fraud risk assessment should therefore be included in the fraud risk management guide, along with recommendations for establishing a comprehensive programme for managing fraud risks. This includes information on developing fraud risk governance policies, implementing fraud preventive and detective control measures, conducting thorough investigations, and taking appropriate actions as required (COSO, 2023).

Figure 7: Fraud Risk Management Process

A fraud risk assessment is a dynamic and iterative process for identifying and assessing fraud risks relevant to the organization. Fraud risk assessment addresses the risks of fraudulent financial reporting, fraudulent non-financial reporting, asset misappropriation, and corruption (including illegal acts and noncompliance with laws and regulations) (COSO, 2023). Therefore, it is imperative for organisations to conduct thorough assessments of fraud risks in order to identify and evaluate specific fraud schemes and hazards. This entails analysing the probability and significance of these risks, evaluating the effectiveness of existing fraud control mechanisms, and implementing measures to mitigate remaining fraud risks.

G. Control Activities

According to COSO (2013), control activities are the mechanisms developed via policies and procedures that support management's instructions to reduce risks and achieve its goals. Furthermore, this is done in companies where expectations are clearly stated and methods for putting these principles into practice are in place (COSO, 2013). According to Chen et al. (2017), the division of work and other constraints are crucial components of control systems that decrease the possibility of income manipulation. Based on Dawson (2015), control activities are precise, evidenced by actual internal checks and balances inside the institution, and frequently take the form of reconciling bank accounts. Control activities, on the other hand, provide two-step risk management, according to Ashfaq and Rui (2018). To accomplish so, management plans for the risks identified during the evaluation, as well as an effective internal control system, must be developed.

H. Monitoring

The efficiency of internal control is assessed through the monitoring process, which can include both continuous and discrete evaluations (Le 2018). Similarly, the IAASB (2018) describes monitoring as efforts made to identify and address shortcomings in the efficacy of financial instrument transaction controls. Monitoring, according to IAASB (2018), also comprises supervision and review methods aimed to detect and rectify faults in control implementation or operational efficacy. As a result, effective monitoring ensures that an organization's internal control system remains effective in keeping it secure (AICPA, 2014). In order for businesses to have effective internal control, according to COSO (2013), it is required to conduct an ongoing, independent evaluation of internal control.

I. Fraud Detection Techniques in Forensic Accounting

Even the most stringent fraud prevention measures can be avoided by a determined and skilled scammer. The implementation of appropriate systems and processes is necessary for early fraud detection. Techniques for detecting fraud can assist in spotting both active fraud and fraud from the past. The two primary ways to identify fraud, according to Dzomira S. (2011), are proactive (like risk assessments) and reactive (like responding to fraud reports), as well as manual (like spot audits) and automated (like specialized data-mining tools). In addition to protecting customers, shareholders, and employees, effective fraud detection helps businesses save money. Therefore, fraud detection should be included in an organization's comprehensive anti-fraud strategy, together with fraud prevention, detection, and investigation. To deter potential fraudsters in the future, the company's detection efforts should be published publicly.

- Reviewing Public Documents and Conducting Background Checks

The records that are freely accessible to the general public are inspected. To find out more about a company's prior business dealings, a detailed investigation into its history is conducted. Public papers also include information in the public database, corporate records, and other legally available internet content.

2. Conducting Detailed Interviews

An important technique for making a difficult subject into a reputable source of information is conducting an interview. It makes sure that all of the information is clearly comprehended. Prior to conducting an interview, it is critical to accurately assess the seriousness of the problem and to plan the questions accordingly. Discussions should take into account all pertinent variables as well as the overall picture to determine the extent of the illegal activities.

3. Gathering Information from Trustworthy Sources

Information from a secret source can be very useful in any situation. When information is obtained through a confidential source or an undercover agent, all necessary precautions should be taken to keep the identity of the purported cause hidden. A forensic accountant should seek as many secret sources as possible as they can because they essentially guarantee an accurate result.

4. Examining Evidence Gathered

By carefully examining the evidence that has been gathered, the perpetrator may be found and the extent of the fraud that was committed in the company can be determined. The research's findings will also be used to assess how safe the company is against financial theft and to put various austerity measures in place to prevent reoccurring problems.

5. Conducting Surveillance

This is one of the traditional methods of detecting any fraud and can be done physically or online. All official emails and messages can be monitored and tracked in order to accomplish this.

6. Going Undercover

This is a drastic action that should only be used as a final option. It's best to let the professionals handle it because they know where and how to perform the investigations. Even a small mistake when operating undercover can cause the criminal to realize something is amiss, at which point they may vanish.

7. Analyzing the Financial Statements

The financial statement contains a summary of all pertinent information, and a forensic accountant can identify the fraud by analyzing these statements.

J. Red flags

Red flags are the results of a number of tests that point to high risk levels in connection to a set of financial statements in the context of accounting (Feroz 2008). The likelihood of committing fraud as well as the option of analytical techniques and ratio analysis exist in a setting with weak controls, which increases the likelihood that fraud will be performed. Kranacher et al. (2011) advise assessing red flags in order to pinpoint potential fraud risk regions. These warning signs do not show that fraud has occurred, but they constitute a warning to auditors that fraud may be emerging indicator that auditors ought to be on the lookout for the likelihood of fraud (Kranacher et al. 2011). All of these approaches have the potential to find anomalies, which will prompt additional research. Red warning flags in the context of accounting are the outcome of a series of tests, the findings of which indicate elevated risk levels in relation to a collection of financial statements (Feroz 2008). Financial statement fraud has a few warning signs that may be connected to different fraud schemes.

Additionally, there might be behavioral warning signs, such an overly rigid way of living. Red flags can be categorized as either environmental or personal fraud signs. Environmental fraud components that may enable a culture of fraudulent behavior include factors relating to the organization, the control environment, and the ethical culture that management has developed. Fraud is more likely to happen in an environment with lax controls since there is a potential to commit fraud, as well as the prospect of not being discovered. If senior management promotes a dishonest culture, it may show in management by dishonest behavior or by putting excessive strain on the staff of the firm by setting unreasonable expectations and goals. Due to the necessity to survive, this could lead to dishonest behavior. Additionally, a fraudulent environment will be fostered if employees think that engaging in fraudulent behavior is acceptable and that they can get away with it (Crawford & Weirich 2011: 354). Because fraud is a crime including the purposeful concealment of some activities as well as the deception of the persons involved (Skalak et al. 2011: 238), red flags are not always instantly evident or easy to recognize and interpret. It is crucial to note that fraud risk variables are not proof of fraud, but rather indicate whether or not fraud has occurred.

- Empirical Review

Numerous studies have looked into the connection between forensic accounting and fraud detection. The research predominantly employs the developed economies of countries such as Canada, Europe, and the United States of America as illustrative instances. The correlation between fraud detection and forensic accounting has garnered significant interest from several African researchers as well. In a recent study conducted by Madzivire E.T. et al. (2020), an investigation was carried out in Zimbabwe to assess the effectiveness of forensic audit as a mechanism for detecting and mitigating fraudulent activities. The research findings revealed a significant correlation between individuals' educational attainment, training background, and capacity to identify and mitigate instances of fraudulent activities. The study conducted by Leonard Mudimba in 2021 aimed to assess the significance of forensic accounting in the detection and prevention of fraudulent activities. Research conducted in Zimbabwe has demonstrated that the implementation of forensic accounting practices within state companies leads to a significant reduction in instances of fraudulent activities.

2. Conceptual Framework

The framework in figure 8 demonstrates the relationship between forensic accounting (independent variables) and fraud detection (dependent variables).

This framework was motivated by Walakumbura, L. and Dharmarathna, D.G. (2022) on the Impact of Forensic Accounting Knowledge on Fraud Detection. Fraud Detection is the dependent variable. Only when each category of the organization's objectives is represented by all of the predefined independent variables and is present and functioning properly can this be accomplished. The proper operation of the independent variables provides a reasonable assurance that the dependent variable will function appropriately. There are different approaches that can assist organisation in fraud detection. The model in Figure 8 below was used as a basis to ascertain how fraud detection in Zimbabwe's public sector will be impacted by forensic accounting's impact on expenditure cycles.

III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The researcher used a descriptive research technique, combining qualitative methodologies with quantitative analysis tools, to analyze data from government ministries' auditing, finance, and administration offices. The study was grounded in a positivist philosophical framework, prioritizing numerical analysis, objectivity, dependability, and reproducibility of findings. The qualitative nature of the study was evident, with a mix of quantitative features and descriptive data. The research used questionnaires and oral interviews to gather data on the feasibility of employing forensic accountants for fraud detection. Secondary data from published audits over the last five years was used to analyze government expenditures. The questionnaires were distributed to professionals in public sector accounting, transforming the data into meaningful information.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. How Forensic Accounting Affects Fraud Detection

It was found out that forensic accounting is a profession that involves applying analytical and investigative skills to settle financial disputes in a way that complies with legal requirements. The goal of a forensic investigation is to establish facts to back up a legal claim. Forensic accounting is a holistic approach to fraud detection that includes non-financial data acquisition, antifraud control analysis, and fraud prevention. It is the use of specialist accounting, auditing, economic, tax, and other expertise to locate and look into suspicious activity. It is feasible to conduct interviews, review documents, go at electronic files, and conduct other kinds of reviews. This research established that forensic evidence must adhere to the requirements set forth by legal authorities and be presented in a manner that will be recognised by a court of law.

B. Practices used by Forensic Accountants in Detecting Fraud

This research established that fraud detection techniques in forensic accounting are necessary to detect both active and past fraud. The two primary ways to identify fraud are proactive (risk assessments) and reactive (responding to fraud reports), as well as manual (like spot audits) and automated (like specialised data-mining tools). To protect stakeholders such as customers, shareholders, and employees, effective fraud detection should be included in an organisation's comprehensive anti-fraud strategy. To deter potential fraudsters in the future, the company's detection efforts should be published publicly.

C. Risk Factors Influencing selection of Forensic Accounting Practices

According to this research, fraudsters and other criminals will go to great lengths to conceal their wrongdoings; thus, firms must address both internal and external fraud threats in order to prevent, detect, and discourage fraud.

Risk Assessment is used to evaluate the risks involved in achieving objectives. Prior to adopting risk management strategies, primary hazards must be recognized. An organisation's specific fraud risks are identified and evaluated through the process of fraud risk assessment. It contains details on setting up fraud risk governance rules, creating and putting into practice fraud investigative and preventative control operations, conducting inquiries, and taking the necessary action. The organisation must therefore perform a thorough assessment with the objective of detecting as well as assessing fraud schemes and risks, appraising their likelihood and applicability, reviewing current fraud control measures, and undertaking actions to decrease residual fraud risks.

D. Fraud Detection Best Practices

The research found that fraud is pervasive, and every organisation should be concerned about the possibility of fraud because any organisation could become a target at any time, for any reason, and for no apparent reason. The government ministries should therefore adopt a variety of actions in order to reduce the likelihood of fraud. This research proved the management's ability to lessen fraud by using the tactics mentioned below:

- The ministries should offer a system for reporting fraud concerns that includes a number of trustworthy channels.

- A suitable policy that informs and nudges stakeholders to report violations should be used to support the system.

- The Code of Conduct should require all government employees to disclose any suspected misconduct, including fraud and corruption. Fraud detection and handling skills should be taught to management and the entire team.

- The management must demonstrate their commitment to encouraging the reporting of misconduct.

- Through appropriate feedback and review activities, the effectiveness of the internal reporting systems should be periodically assessed against updated risk assessments.

- The public sector should impose individual responsibility and legal action against all offenders.

- Regular internal audit inspections, due diligence procedures, staff training on frauds, and information sharing with other ministries should all be used to tighten internal controls.

V. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The successful completion of this work would not have been feasible without the invaluable direction, support, and assistance provided by the following individuals over the course of the research. I received important instruction and feedback from Mr. Bhibhi and Mr. Mazhindu, both affiliated with Midlands State University, Zimbabwe, as well as Mr. Ronald Chiwariro from Jain University, India. I would like to express my gratitude to Mrs. B. Murinda for her invaluable moral support during the study process. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge Lieutenant Colonel Mbinya the Deputy Director Zimbabwe National Army Finance for providing useful guidance during the field work. The cooperation of the Finance, Administration, and Auditing personnel from various ministries including Defence and War Veterans, Finance, Home Affairs, Foreign Affairs, Sports, Tourism, Local Government, Justice and Legal Affairs, Primary and Secondary Education, Small and Medium Enterprises, Higher Education, as well as participants from the Auditor General Office, who were involved in this study, is also acknowledged and appreciated for their valuable contribution during the process of data collection.

Conclusion

The study reveals a significant gap between forensic accounting and standard auditing in Zimbabwe\'s government institutions, despite the prevalence of fraudulent activities. The paper posits that the utilisation of forensic accounting techniques has the potential to facilitate the identification of fraudulent actions within the public sector. Both internal and external auditors within the public sector are responsible for producing auditing reports, with their primary duty being to furnish an audit opinion. The paper proposes that the government should establish a linkage between its organisational structures and forensic accounting services in order to enhance autonomous operations without any interruptions. Additionally, the establishment of well defined policies is necessary to govern the execution of forensic accounting practises. The accuracy of the study was constrained by factors such as participants\' level of sincerity and the reliance on questionnaires. It is advisable to conduct additional research on the impact of internal controls on forensic accounting techniques.

References

[1] ACFE, Report to the nation 1996, 2002, 2004,2008,2022 (USA). [2] AICPA and ACFE Join Forces to Prevent Fraud. Journal of Accountancy, Jan 2007, Vol. 203 Issue 1, p32-33. [3] Alan Bryman & Emma Bell (2007): Business Research Methods. Oxford University Press [4] Bologna, G.J. and Lindquist R.J. (1987). “Fraud Auditing and Forensic Accounting: New Tools and Techniques”, Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Publication. [5] Cain, S. (1999). Fraud in the workplace. Orange County Business Journal, Vol. 22, No, 16, pp. 78. [6] Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) [7] Sarbanes Oxley Acts (SOX), 2002 Sequence Inc: Are we really getting tough on Financial Fraud by Tracy L. Coenen. [8] The Fraud Examiners: http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2023/Oct/TheFraudExaminers.htm. Accessed 07 October 2023. [9] The state of schemes, ten things about financial statement fraud, 2nd edn. Deloitte Forensic Center, http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2023/May/StateofSchemes [10] Walakumbura, L. and Dharmarathna, D.G. (2022) Impact of Forensic Accounting Knowledge on Fraud Detection. Volume 9 issue 1 (2022) Journal of Accountancy and Finance. [11] Zimbabwe Government Treasury Circulars

Copyright

Copyright © 2023 Gibson Tangai Murinda, Ronald Chiwariro. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET57067

Publish Date : 2023-11-27

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online